Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Community-led retrofit can deliver more than energy efficiency

Birmingham’s local initiatives are harnessing neighbourhood resources to deliver retrofit while boosting engagement and civic pride, writes Simeon Shtebunaev

Simeon Shtebunaev is an interdisciplinary researcher in the built environment working at Social Life. Their PhD project at Birmingham City

...moreThe challenge to retrofit ageing building stock is immense. The Green Alliance report, Reinventing Retrofit shines a light on the fact that, with just 13 years to go until 2035 – when the UK aims to have retrofitted all properties to EPC band C – only 29 per cent of UK housing stock meets the standard. With a challenge so big and a lack of coherent government policy and support, community-led approaches are increasingly seen as a way to plug the gap, delivering the benefits of a decentralised, localised and scalable enterprise.

The European Commissions’ Renovation Wave, part of the European Green Deal, puts citizens and neighbourhoods at the centre of its drive to retrofit buildings, create jobs and improve lives. Back in the UK, no such national strategy exists, but more and more community-led initiatives are sharing lessons and building case studies, and a movement is emerging. To maximise the potential of such initiatives, it is important to understand the challenges and opportunities they face.

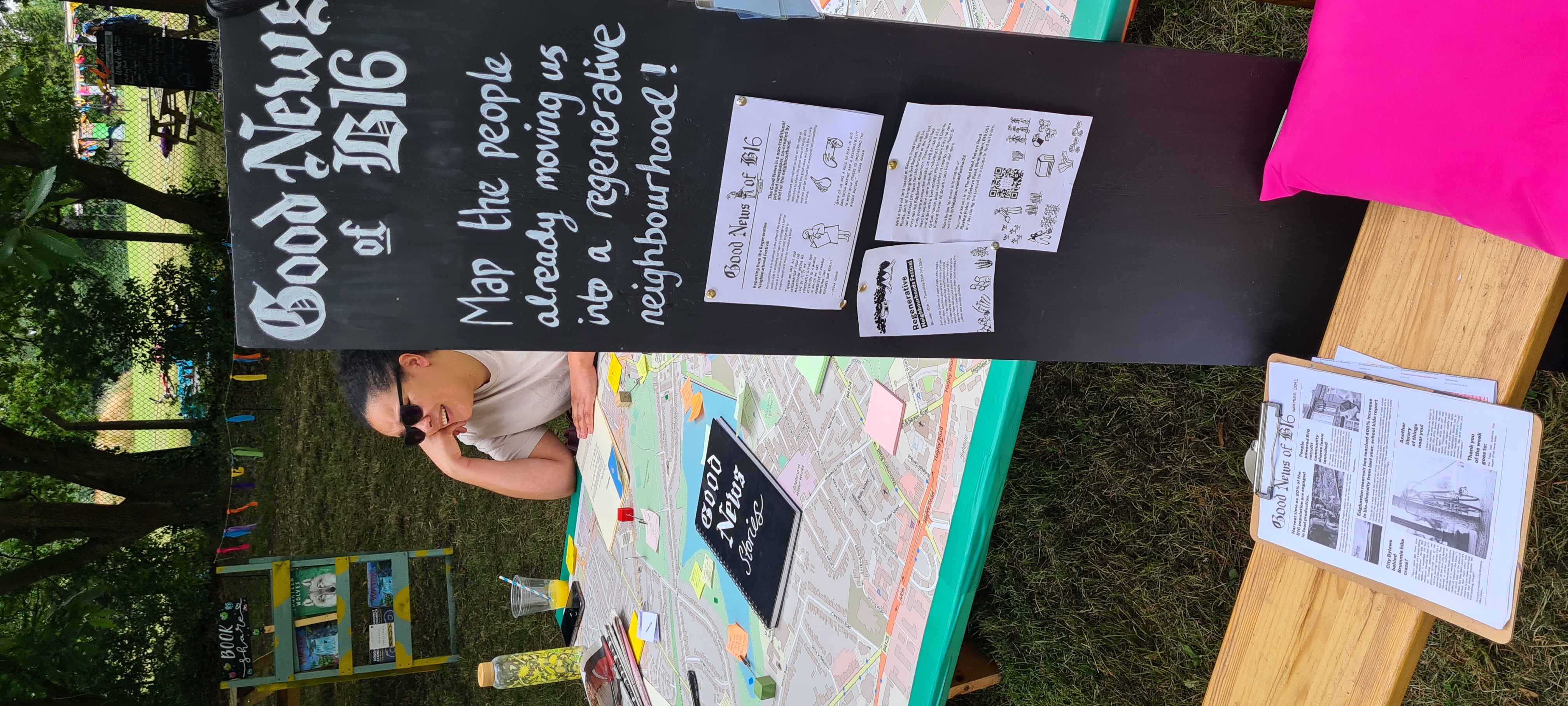

In July 2022, the Retrofit Reimagined festival was held on the banks of Birmingham’s Edgbaston Reservoir, organised by Civic Square in partnership with Dark Matter Labs, Architects for Climate Action Network (ACAN) and Zero Carbon House.

The four-day festival welcomed practitioners, organisations, communities and individuals working within the field to “establish solidarity, share knowledge and resources and galvanise collective momentum around more equitable, creative, collective approaches to decarbonising the built environment, reimagining retrofit from being one of our biggest challenges to one of our greatest opportunities to transition equitably together”.

Civic Square, a community building organisation which operates out of Port Loop in Birmingham, has adopted Link Road – a typical, Victorian street of terraced housing close to its headquarters. Working with Link Road’s residents, this street is a test bed for what retrofit can mean to a community, beyond the tech-driven focus.

Civic Square has adopted Link Road - a typical, Victorian street of terraced housing in Birmingham. By working collectively with its residents, a test bed for what retrofit can mean to a community is emerging beyond the usual tech-driven focus

Also in Birmingham, in Balsall Heath, home of the Zero Carbon House – the first net-zero retrofit in the UK, designed by architect John Christophers – a neighbourhood-based initiative, Retrofit Balsall Heath, has the bold aim of mobilising and securing funding for the retrofit of housing stock in one of the poorest wards in the country. These two small-scale and community-led initiatives, Link Road and Balsall Heath, have bold ambitions, working with organisations embedded within the construction and development industry, with the potential to export their localised learnings to a national level.

When we think of community-led retrofit, we can fall victim to the terminology and narrow down the vision to a series of domestic upgrades by collectives defined by their geographic proximity. However, communities of practice are also emerging as important drivers of this change. ACAN’s Existing Building group is one such network, focusing its work on collecting case studies, developing research evidence and implementing action. The Households Declare! initiative set up by the group is aimed at individual households, so as to educate, inspire and implant the seeds of community-led retrofit action across the country.

We also need to understand that the ambitions of community-led initiatives can vary widely. Do they target an individual street or a whole neighbourhood? Is their goal net zero? What is the focus – domestic or community, holistic or incremental, retrofit or repurposing? Each variation presents unique challenges.

A paper by Tobias Putnam and Donald Brown in the Energy Research and Social Science Journal sees grassroots retrofit initiatives as a potential key delivery partner for local authority fuel poverty schemes. The benefits of such initiatives include increased engagement, better supply chains, skills development and accurate targeting of fuel-poor households. However, the paper observes a limit in the scaling of such initiatives in the absence of a coherent government policy.

Another key barrier is access to capital. Community-led retrofit schemes still largely rely on government grants and support. The UK tax framework imposes 20 per cent VAT on retrofitting projects, as opposed to new-builds, further diminishing the prospects of communities being able to raise funds in a targeted manner.

Additionally, current local government schemes under the Green Homes Grants programme, such as the West Midlands Warmer Homes initiative (the target of the Retrofit Balsall Heath community group), impose financial eligibility requirements. To qualify, households must have a combined gross household income of less than £30,000 (including benefits) and a home Energy Performance Certificate rating of D, E, F or G to qualify. This questions the eligibility of properties in a given neighbourhood and diminishes economies of scale. Furthermore, fuel poverty is about the percentage of income spent on heating, meaning that there are fuel-poor families who are ineligible for government grants – providing additional challenges for community organisers.

Another issue for community-led initiatives is governance. Such initiatives are no stranger to the traditional issues of citizen organisation, mobilisation and execution. It would be wise to cast an eye on the results of another national community-led initiative instigated by the government: neighbourhood planning. Community-led retrofit faces a lot of the operational challenges that neighbourhood planning, with the added challenge of the absence of a regulatory and policy framework.

Andrew Karvonen writes in the book Retrofitting Cities for Tomorrow’s World that community retrofitting can develop local identity and civic pride, as well as fostering community cohesion – words similar to the aims of the localism and levelling-up agendas. In their review to the government in 2020, Impacts of Neighbourhood Planning in England, Gavin Parker summarises key barriers: a downward trend of uptake by communities, burdensome process, resource burden on local stakeholders, lack of willing volunteers, lack of local planning authority support and engagement, and generally long timeframes.

Fuel poverty is about the percentage of income spent on heating, meaning that there are fuel-poor families who are ineligible for government grants

The planning system has also been reported as an obstacle. Suzy Nelson, part of the ACAN Existing Building group, is researching the experience of winning planning for schemes incorporating retrofit works and renewables. Nelson is seeking to understand whether planning or professional processes, such as the RIBA Plan of Work, accommodate retrofit.

Power and ownership are another underlying issue. Asked what the chief obstacle is holding back community initiatives, Scott McAulay from the Anthropocene Architecture School unequivocally identified it as households not having the power to say yes to retrofit. According to the English Housing Survey 2019-20, 4.4 million households in the UK rent privately and another 4.0 million live in social rented accommodation. This equates to 36 per cent of UK English households likely lacking the power to agree to works being done to their accommodation. Combined with the restrictions of the Green Deal grants, which expect landlords to contribute upwards to 50 per cent of the costs, lack of tenant-ownership can become a barrier to community-led retrofit schemes.

The intrusive nature of retrofit practice also poses questions in diverse communities, where they may disturb religious and cultural observances. Ambitions for a net zero carbon neighbourhood in Balsall Heath are supported by locals including Kamran Shezad from the Sultan Bahu Trust, who is also involved with Footsteps – Faiths for a Low Carbon Future, a pan-religious organisation. The church and the mosque, the traditional hosts of the planner’s consultations, are now providing a new space, hosting debates about communities. Retrofit Balsall Heath hosts its Climate Café meetings at the MECC – a Muslim-led organisation in the neighbourhood.

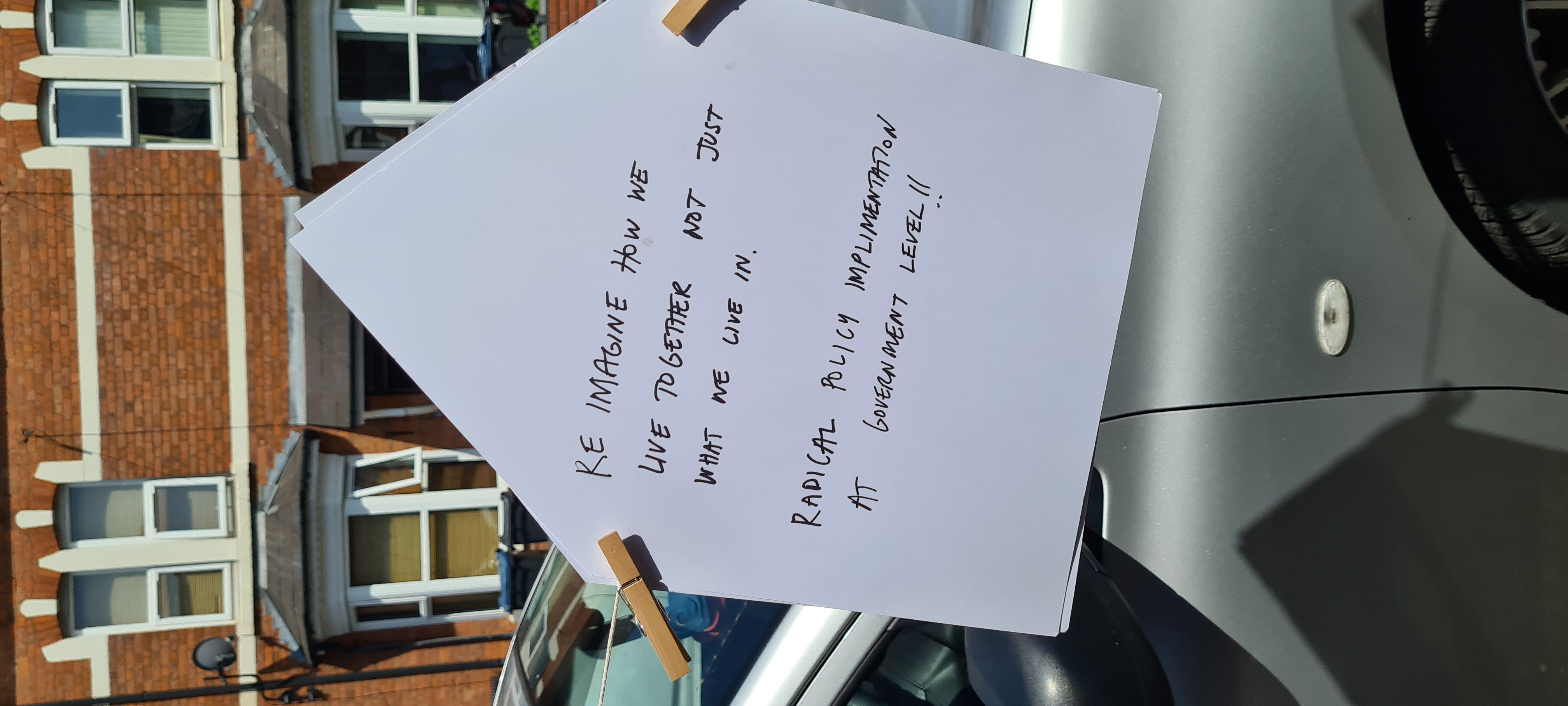

One question being asked by community-led initiatives is whether we’re approaching retrofit through too narrow of a technological lens. Writing in the Building Research and Information Journal, Kirsten Gram-Hanssen suggests if homes are owned, occupied and retrofitted by the same people, then we need to reframe approaches to consider the human dimensions of retrofit.

Gavin Rogers, an artist and resident at Link Road, goes further. “We should use this opportunity to retrofit our communities,” he says. In a video about his home, part of the Retrofit Reimagined Festival, Rogers paints a picture of the diverse community that occupies Link Road and current challenges: gentrification, rising housing and rent prices, drugs and community cohesion. Instead of judging the complexity of interactions that exist in his neighbourhood, he points out the need to capture the community’s imagination by addressing day-to-day living conditions – a comprehensive approach to retrofit that respects the social fabric of the neighbourhood.

Community-led retrofit presents opportunities for a wholesale rethink of architecture and planning. By challenging the culture of development, the Birmingham initiatives are aiming to create agents of change out of residents; to reimagine not just the physical fabric of the buildings but the social and environmental threads woven around them.

Learning can present an opportunity to galvanise communities, and especially young people, in understanding the built environment. Retrofit captured the imagination of 13 youths aged 14-18 from Balsall Health who, over the space of two months in 2022, developed a board game focusing on educating through play. The game, Climania, is a free-to-download engagement tool that informs people of the built environment’s role in the climate emergency. Led by Birmingham City University academics and GAP Arts, the game has fostered a community network and has served as a tool of engaging through play with residents, politicians, and activist groups. Engagement through play can answer some of the key challenges community organisers face; How do we convince people of the benefits of retrofit? How do communities get together? How do we simplify knowledge distribution?

Community-led retrofit strategies might struggle to scale or to be the definitive solution to the challenge of retrofitting the nation in a hostile policy and economic environment. But retrofitting can be the strategy around which neighbourhood-developed power is concentrated and communities coalesce

Learning through experience is another tactic. Civic Square has developed a fruitful partnership with the Centre for Alternative Technology in Machynlleth, Wales. Trips to the centre for local residents, professionals and community activists have proven a powerful tool in intergenerational education, fostered through collective excitement. In Link Street, Scott and Eleanor Hewer have opened their home to everyone in their community. They have welcomed Sustainability West Midlands consultants, facilitated by Civic Square, to map and conduct retrofit assessments and, in the process, explain the specifics to gathered neighbours. Finally, the Zero Carbon House based in Balsall Heath has been an exemplary project, opening its doors to community members and acting as a demonstrator project.

If most bottom-up and third-party domestic community-led retrofit schemes are at early stages, community-led retrofits of publicly accessible buildings have emerged across the nation. Kinver Sports and Community Association in Staffordshire, working with the Rural Community Energy Fund, has undertaken a zero carbon project to retrofit its 1970s building to upgrade its energy performance. Further west, Swansea-based charity Awel Aman Tawe has bought the former Cymgors Primary School in south Wales and is aiming to renovate it into a zero-carbon, arts, education and enterprise centre for the local community. In the home of urban gardening project Incredible Edible, Todmorden Learning Centre and Community Hub has acquired Tod College, previously council-owned, which it plans to retrofit. In the process, it will also train local young people in natural building, agro-ecology and renewable energy systems.

Developing retrofitting skills is a way of overcoming many of the challenges that communities face beyond initial learning and engagement. As Ellen Robottom and Wolfgang write in Climate Jobs: Building A Workforce For The Climate Emergency, a mass retrofitting programme will require a large and skilled workforce across the country. Economic empowerment is a key part of the puzzle. The number of retrofit coordinators and trained contractors is currently insufficient but community-led initiatives are aiming to fill the gap.

In Greater Manchester, organisations such as Carbon Co-op and URBED support the not-for-profit service People Powered Retrofit, which aims to support those who want to retrofit their property. Almost a decade old, in rural Tipperary, Ireland, the Energy Communities Tipperary Cooperative (ECTC) is another community-led home renovation and retrofitting organisation providing a one-stop-shop service, eliminating many of the challenges people face in the process.

Community-led retrofit strategies might struggle to scale or to be the definitive solution to the challenge of retrofitting the nation in a hostile policy and economic environment. But retrofitting can be the strategy around which neighbourhood devolved power is concentrated and community groups coalesce. We can use the retrofit strategy to deliver on some of the neighbourhood planning agendas, high street regeneration and community cohesion projects that have struggled over past decades. When communities are involved, retrofit is about more than the energy efficiency of a single dwelling; it’s about connections, health, wellbeing and place.

Simeon Shtebunaev is a doctoral researcher in youth, urban planning and future cities at the School of the Built Environment, Birmingham City University. He is RIBAJ Rising Star 2021 and RTPI West Midlands Young Planner of the Year 2021. Shtebunaev is also founder of Urban Imaginarium – a consultancy focused on empowering young people.

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238