Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox Yes, please!

Why are we building homes in high risk flood zones?

Since April 2016, 2,947 homes have been given planning permission against Environment Agency advice. What is going wrong? Peter Apps reports

The countryside outside Scunthorpe is flat and low. You can see the horizon, which is often a canvas of slate grey clouds at this time of the year, and a patchwork of green and yellow and brown agricultural land, with the River Trent winding through the landscape towards the Humber.

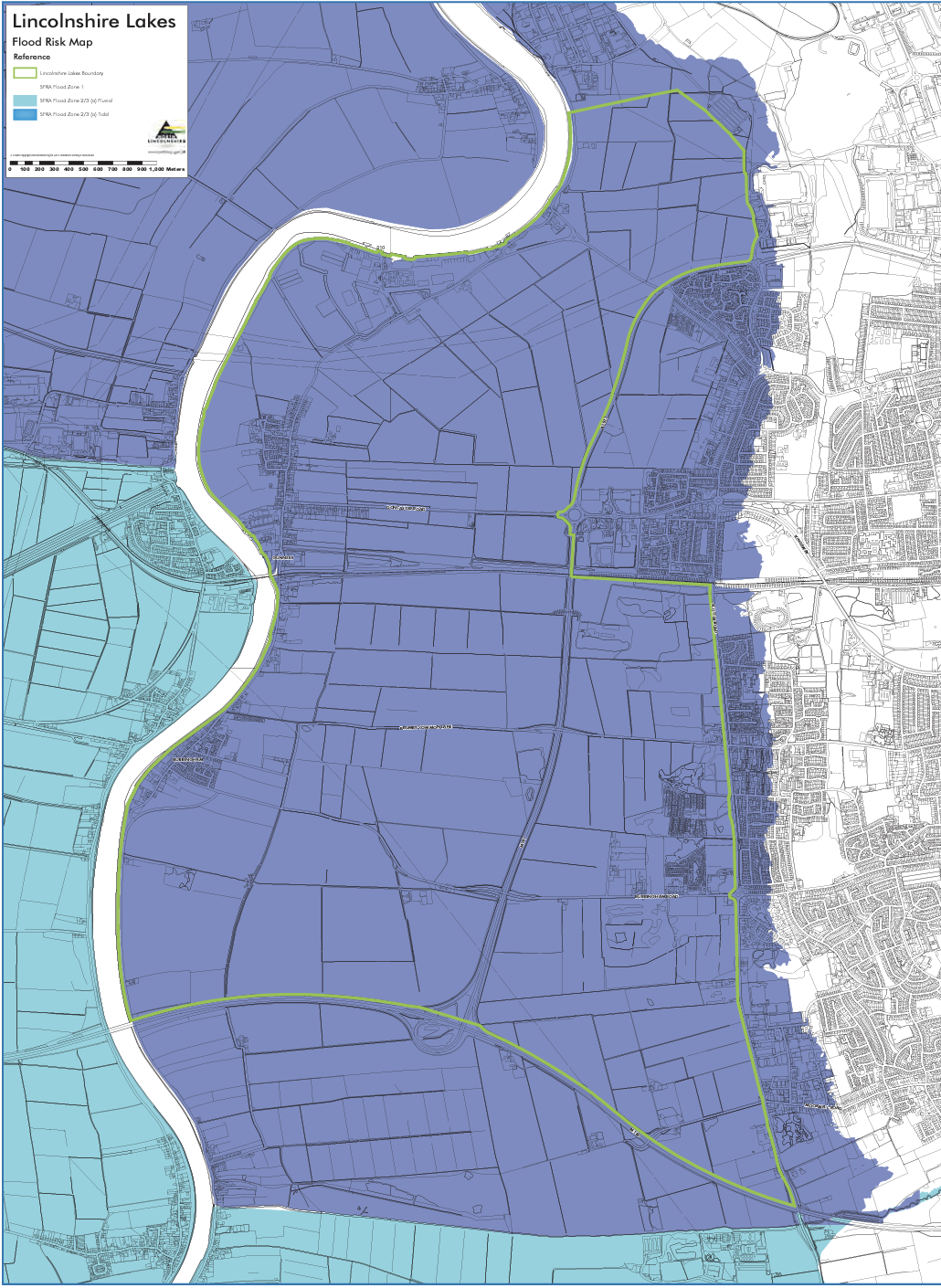

There are big plans for this land. Since 2003, it has been identified as a site for major residential development - the Lincolnshire Lakes will provide 6,000 homes linked into six garden villages. Like many of the big planned urban developments on greenfield land, it has so far been a case of big promises and little actual building. One of the main reasons it has been held back is the fear of flooding.

Lincolnshire is one of the most vulnerable areas of the UK to floods. The area lies five metres below sea level in some places. Just last month Storm Babet saw 170 homes flood as a month’s rain fell in 24 hours. News images showed dirty brown water lapping around restaurant tables as rivers broke their banks in Lincoln.

There were concerns that some existing flood defences did not work as they should have, with an investigation launched by the Environment Agency. So why in this context are we even considering adding another 6,000 homes to an existing flood zone in this area?

There is no law in the UK against building in a high flood risk area

The answer is one of the other major problems plaguing the UK. We need them. Scunthorpe is struggling economically. The city is still heavily reliant on its steelworks for decent paid work, and faces 2,000 redundancies as British Steel closes the furnace. In this context, the boost that a major, desirable development would give to the town is incalculable.

The developers think the scheme will mitigate the flood risk. Planning laws designate the site as a mix of flood zones 2 and 3a, which means they are at a medium and high probability of flooding. It is one of the largest developments in the UK in such a high-risk area.

A detailed flood mitigation strategy has been developed, based on a combination of flood defence improvement works to the River Trent and land raising of the proposed development area. The lakes and wetlands incorporated into the development are also designed to help reduce flood risk.

But will this be enough, as the ravages of climate change enhance the risk over the next century and beyond? This development exemplifies a challenge that will become more and more critical to urban planning. How do we make sure what we are building is safe from flooding?

The system is not working as it should... The Environment Agency has no actual enforcement power

There is no law in the UK against building in a high flood risk area. Instead, the planning system is supposed to prioritise development elsewhere and place conditions on what is built to ensure it is safe.

But data suggests this system is not always working as it should. The Environment Agency – a government body which can make recommendations on planning decisions but has no actual enforcement power – publishes statistics on whether its recommendations have been followed. They show that since April 2016, 2,947 homes have been given planning permission against its advice. What is going wrong?

Planning law splits the country up into three zones with regard to flooding: zone one is low risk and two is medium risk. Zone 3 is split into ‘a’, which is a high risk area but one you can potentially build houses on and b, which is a functional floodplain, where you cannot.

But this is where we hit our first problem. The zones are split up according to what happens in a ‘one in 100 year’ flooding event, with some enhancement to the property to take into account climate change. But this is based on past data, and we are entering a new climate.

“Hydrology, the science of understanding how the rain falls and then the flow that results in a river has always been based on historic data,” explains Jonathan Morgans, director of water environment at Hydrock.

“We would always develop what we think is the one-in-100-year flood, or the 1% annual probability flood, from our understanding of all the floods that have happened before. If our climate is shifting, then effectively it starts to undermine our understanding of hydrology.”

“The starting point has to be what will good look like in 10, 20 or 50 years time, not what it looked like over the last 20 years,” adds Paul Cobbing, former chief executive of the National Flood Forum and a consultant.

More than 5,000 homes in flood risk areas were given permission in 2021 alone

Modelling this is not straightforward. We know that warmer air holds more moisture, which means heavy rain events will get more frequent and more intense as climate change continues.

But this is not necessarily a simple linear progression: the changes are also messing with systems like the jet stream, which have an enormous impact on our rainfall. Who is to say a one in one hundred year flood won’t become one in 20? Or that the one in a hundred flood will be much more intense than we anticipate?

This makes building in flood risk areas a big gamble. But it is still something we do a lot of. Research by the insurance industry in November 2021 showed that more than 5,000 had been given permission in that year alone.

Joe Fyans, head of research at the think tank Localis, has looked into this issue. “Most of these [developments in Flood Zone 3] are micro developments of less than nine houses,” he says. “But the problem is they are all being considered individually. What the system does is just look at the eight houses being proposed and say they’ve got good flood defences. But you’re still increasing the aggregate risk of surface flooding and runoff elsewhere.”

And the system does not always function as it should. If a developer proposes a residential development in Flood Zone 3, they should carry out a sequential test - looking at all other developable land nearby to see if there is somewhere else it could go. But this is not always properly enforced.

One planning consultant based in the West Midlands, who asked to stay anonymous, told The Developer: “When you mention a sequential test, the developer will say do we have to do that? I get that almost every day. So we’ll do the report. We won’t mention sequential testing. And therefore, we let the other side [the planning authority] remember to enforce that. And they often don’t.”

One planning consultant said that often the planning authority will fail to enforce sequential testing

Even if a sequential test is done, exactly what goes into it isn’t easily defined. Really, it should be the local planning authority that decides the ‘catchment area’ for the test, but the developer’s consultants will sometimes take this on themselves - and draw it very narrowly.

“The catchment area and how you define it is down to the planning officer’s discretion,” says the consultant. “But I don’t think planning officers always realise they’ve got that power, so they will follow the consultant’s report.”

This taps into a bigger problem in the development world: planning officers are horribly under-resourced and understaffed.

In a survey by the Town and Country Planning Association in 2020, just 12% of local authorities strongly agreed that they have the skills and expertise to take account of flood risk now and in the future in planning decisions.

“The extent to which planning authorities can properly police all of the regulations around flooding is, I think, open to debate given their capacity constraints,” says Fyans.

Local authorities are too reliant on consultant reports which could be deliberately incomplete

One of the tasks for the planning authority is to review the flood risk assessments which the developer’s consultants have written. Again, this is something which is not always done in the best faith.

“There’s no development opportunity that will come to the office that someone is going to say an outright no to, we will always write the report,” says the anonymous planning consultant.

They add that once a developer has drawn up a plan which gives, for example, 100 houses, they are deeply reluctant to lose any of them.

“Anyone who says anything that is reducing that number is a problem, as far as the developer is concerned,” says the consultant.

The result is newly built properties at risk of flooding. “I have spoken to people who live in newly built properties who have been unable to get insurance because of the flood risk. That shouldn’t be happening,” says Cobbing.

What about the homes built against the Environment Agency’s advice? Sometimes these are due to simple failures to provide the right documentation. A 231-home development in Kirkham, Lancashire, for example was subject to an objection from the EA because the developer had not provided proper drawings showing the relationship between the site boundary and the eight metre easement zone for a nearby river.

But in other instances they are far more substantial. A major 475-home conversion of a recycling depot in east London was given planning permission by the body responsible for developing the land around the Olympic Park in 2016, despite the EA warning it had “a high probability of flooding” with “unacceptable” risk to life.

Even where the EA doesn’t object, its concerns can be serious.

Albert Road in Newham, east London, is one of the capital’s more deprived areas. It sits on the way to a free ferry which carries heavy lorries across the Thames, and under the flight path to London City Airport. It is also between two major bodies of water: the River Thames and the old docks in Silvertown, which puts it in Flood Zone 3. It sits outside the defences of the Thames Flood Barrier.

Permission has been granted for homes despite warnings from the Environment Agency of an “unacceptable” risk to life

In 2019, MGL Architects applied for planning permission to construct - a four storey block of flats - which was approved. This was despite the agency warning that “a breach in the tidal flood defences, while a relatively low probability, could have a devastating impact due to the depth and velocity of the flood water”. It called for additional flood defences and no bedrooms to be permitted on the ground floor. This was first reported by Bloomberg, and confirmed by planning documents seen by The Developer.

But who will enforce this, if and when the development is eventually built and occupied?

Around the corner, a huge 350 home development is being built just on the river’s edge. Here, the Environment Agency did not object, noting that while the scheme was at risk of flooding “the developer has not proposed any sleeping accommodation below the modelled tidal breach flood level”.

Walking around the area there are plainly other developments with ground floor flats - some of them relatively recently built. At some point in the next 100 years this area will likely flood and water will sweep in from the Thames on both sides. Heaven knows what will happen to those who live here when it does.

There are important matters which are outside the EA’s remit. The agency deals with the risk of ‘fluvial’ (river) flooding, but a growing risk is surface water flooding, made more frequent by extreme rainfall events caused by climate change.

This is where rainwater simply overwhelms the drainage system. It is particularly difficult, because it can happen anywhere the rain falls. London – with its aging Victorian sewage system and its ever expanding population – is particularly vulnerable to this risk.

SUDS requirements are coming, but long overdue

But development is often a contributor - not only adding to the population using the drains, but removing permeable surfaces through which water would otherwise drain.

Here, change is coming but it is overdue. Next year ‘sustainable drainage system’ (SUDS) requirements will become compulsory. These will require developers to incorporate SUDS features into their developments which will allow water to drain through the site without simply flowing into the sewers - water butts, rain gardens, ponds, permeable surfaces and swales (shallow ditches) will be required.

But these rules are late arriving. The Flood and Water Management Act 2010 could have introduced the rules in full, but omitted some key parts. They were imposed in Wales five years ago. But England has continued to lag behind.

Sue Illman, managing director at Illman Young, says this change does not necessarily have to result in more expense or fewer homes, but does need to be considered at an early stage by developers.

“You need to design it from the start,” she says. “You have to understand what direction the water will flow down through the site. And if you understand that, you can manipulate it to a certain extent to enable you to design a system that takes the water where you need it to go.”

But even if the SUDS legislation works, it will not affect the many ‘permitted developments’ that sit outside the planning process. These are not major housing developments, but anything that takes permeable land and makes it impermeable increases flood risk, such as concreting over a front lawn to provide car parking.

“What would have been a soft surface permeable soft surface has now become a hard surface. When it rains water shoots off that surface into the gutters. And then the local sewage system becomes overwhelmed,” explains Richard Coutts, a director at Baca Architects and a leader in the field of designing flood resilient projects.

Coutts says we should adopt a “marginal gains” approach - looking for places where we can store water as flooding increases.

“Having sewage in your home – because that’s what it means to be flooded – breaches your castle, it breaches your self confidence”

“So for example, if you’re considering paving over your drive to park your Tesla to recharge it, you could be required to fit a water storage tank underneath it to maintain similar levels of water storage. That wouldn’t be too expensive, but the cumulative effect of that across the nation would be significant,” he says.

As for the EA’s plans, announced in 2020, to protect thousands of homes from flooding through major flood defence works delivered by 2027, the National Audit Office has revealed that a quarter of these works have been cut – slashing the number of homes protected from 336,000 to 200,000.

We need to start thinking more about flooding as not just a property issue, but a human one.

“I regularly get calls from people who were flooded in 2007,” says Cobbing. “Having sewage in your home - because that’s what it means to be flooded - breaches your castle, it breaches your self confidence.

“There are people who don’t go on holiday, and people who, if they are away from home and it starts to rain, they will go home. Others wake up in the middle of the night and look at the drains and gutters and everything else to make sure they’re clear.

“There is a link between flooding and poverty,” he adds. “Poorer people are less likely to have contents insurance and will struggle much more to get back on their feet. They might not have a landlord who supports them, and they can get driven into a cycle of problems.”

More of this is coming with climate change. The built environment should work to ease the burden, not add to it.

Peter Apps is an award-winning journalist and author of Show Me the Bodies: How we let Grenfell happen. The book was awarded the Orwell Prize for Political Writing in 2023. Apps is a contributing editor of Inside Housing

If you love what we do, support us

Ask your organisation to become a member, buy tickets to our events or support us on Patreon

Sign up to our newsletter

Get updates from The Developer straight to your inbox

Thanks to our organisation members

Become a member

© Festival of Place - Tweak Ltd., 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. Tel: 020 3326 7238